“The best way to predict the future is to create it.” — Abraham Lincoln

In a world of information overload, how can businesses cut through the noise and connect with their audience on a deeper level? The answer lies in the power of storytelling. But not just any story. You need a strategic narrative, a carefully crafted vision that inspires action and shapes the future.

In this article, we’ll break down what a strategic narrative is and why it matters. Most importantly we’ll show you how you can start building one today to give your organization a competitive edge.

A great example of a strategic narrative in action involves space travel. After many years of stagnation, billionaires and their private companies are investing heavily in making space travel cheaper and safer than ever before.

Here are two of the leading companies, SpaceX and Blue Origin, and their vision statements.

Both companies are trying to shape the future of space travel. But they have two quite different ideas about why humans should go to space.

Blue Origin dreams of helping the Earth through space travel, tethering its mission close to home. SpaceX, on the other hand, reaches for the stars, driven by a bold vision of making humanity an interplanetary species.

Which future captivates you more?

I have a clear favorite here, but first, let’s dissect what strong, strategic narratives are all about. We’ll return to this example at the conclusion of the article.

Here is what we will cover:

- What is a strategic narrative?

- Story vs. narrative: Why the difference matters

- A single strategic narrative vs. a constellation of narratives

- Strategic narratives and North Star narratives

- Why do strategic narratives matter for businesses?

- How to define strategic narratives with narrative maps?

- Case in point: SpaceX vs. Blue Origin

As the cofounder of a fast-growing company, I’ve spent many years in marketing and communications. I’ve grown increasingly excited about the power of narratives. That’s why I’ve researched the topic for more than two years. The result is a book I’ve written about it, called The Narrative Age.

My goal with this article is to make some of the most impactful concepts from the book easy to access and understand. I would greatly appreciate any feedback on how this works for you and what could be improved in the future. But for now, let’s get started!

What is a strategic narrative?

A strategic narrative is a shared vision of the future. If compelling enough, it will gain the support of more and more people. Eventually, it will be more than just an abstraction. People will begin to see the strategic narrative as though it already exists. As Peter Senge, author of The Fifth Discipline, wrote, “Few, if any, forces in human affairs are as powerful as a shared vision.”

Why not just call it a strategic “vision” then?

The concept of a narrative introduces something more powerful than simply having a vision of the future state of the world. Why?

In a business context, the ultimate destination of a vision isn’t your company website, a corporate slide deck, or a framed poster in the main lobby. It’s the minds of the people whom the company unites behind a common objective.

Creating a palpable vision is about changing people’s minds, and we all know how difficult this can be. But there is a powerful concept that can help: storytelling.

What makes stories powerful?

Stories play a crucial role in this process. They provide our brains with a shortcut to understanding cause-and-effect relationships without having to experience potentially dangerous or resource-draining situations firsthand. The same logic applies to an organization and its employees or customers.

Employees will listen to stories of current or former employees to learn if a potential workplace is worth investing their time and energy. Customers will use forums or review sites to hear stories and experiences about your product or service to determine if it is worth buying, and so on.

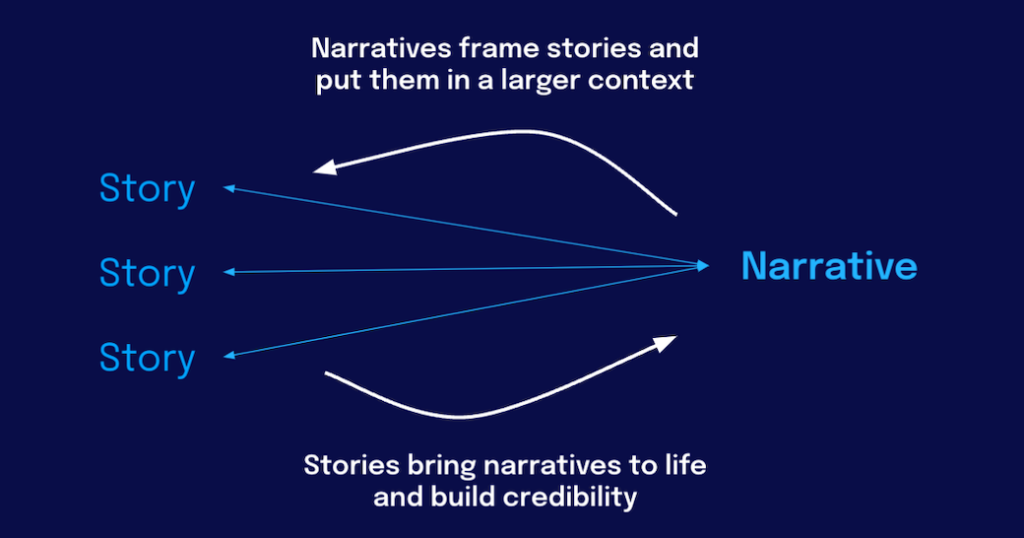

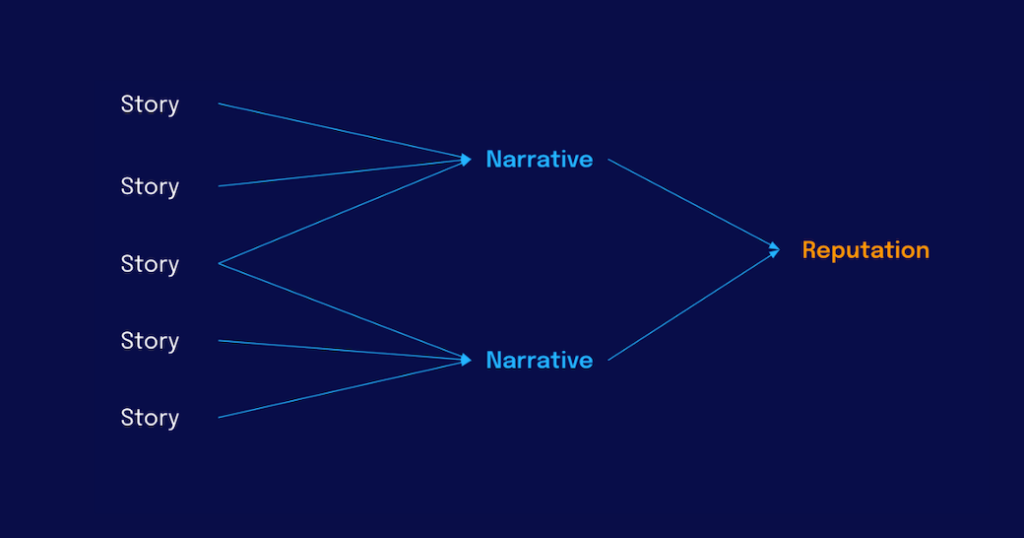

However, while stories are powerful, taken individually, they are too tactical and specific to build a long-term vision. To consolidate the power of many individual stories requires them to have an overarching layer: a narrative. As such, a narrative is different from a story.

Story vs. narrative: Why the difference matters

People often use “story” and “narrative” interchangeably, but storytelling and narrative are different concepts.

Narratives are patterns that emerge from multiple stories.

Stories and narratives share common elements. The most important is their basic structure — they have a beginning, then something happens, and then there is a new end state. This structure is immensely helpful if you want people to follow a vision. It’s not just about where you want to go (the end state), it’s also about the journey of getting there.

How narratives move beyond stories

Stories and narratives differ in their level of abstraction. Stories are very specific, while narratives are more general. Let’s consider, for example, the classic tale of the underdog. The movie Rocky tells one of the most famous underdog stories ever.

Beginning: Rocky Balboa, a boxer from Philadelphia, struggles with life’s complexities and his own self-doubt while dreaming of a better future.

Middle: Seizing an unexpected opportunity, Rocky prepares to fight the heavyweight champion, Apollo Creed, undergoing rigorous training that tests his limits and builds his confidence.

End: Rocky goes the distance, losing the fight by a narrow margin but winning the respect of the audience and proving to himself that he has what it takes to be a contender.

You could summarize the narrative behind this underdog story like this:

Beginning: The underdog emerges from humble origins, burdened by adversity but marked by unacknowledged potential.

Middle: Through trials and relentless determination, the underdog confronts and overcomes obstacles, undergoing significant personal growth.

End: Culminating in a hard-fought battle, the underdog’s journey concludes with a moral victory that underscores the resilience of the human spirit.

Writers depict story characters like Rocky Balboa as individuals with distinct personalities. At the narrative level, they portray these characters more as types of people or groups, such as underdogs.

So now that we understand the difference, why should you think about a “strategic narrative” and not a “strategic story?”

Because only narratives have the real power to create a movement.

Stories are mostly about what happened to other people. Rocky Balboa might be an inspiring character who makes an emotional connection, but his story never becomes one’s own.

Narratives, on the other hand, are inclusive — they can become one’s own. The narrative of Rocky can inspire me to work hard and achieve success. Maybe not as a boxer but perhaps as an entrepreneur. While stories are about other people’s experiences, narratives invite each of us to be participants. That’s what makes narratives are so powerful.

Let’s summarize:

A strategic narrative is a vision about a desired future that an organization is working towards. It includes not just an end state but focuses on the journey. Multiple stories contribute to the same narrative, forming a pattern rather than confining it to a single specific story.

A single strategic narrative vs. a constellation of narratives

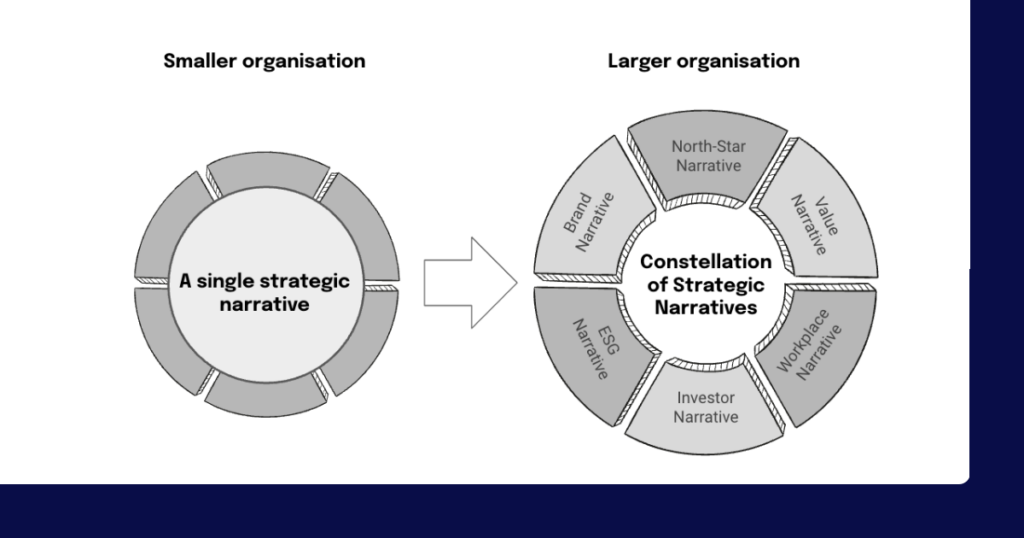

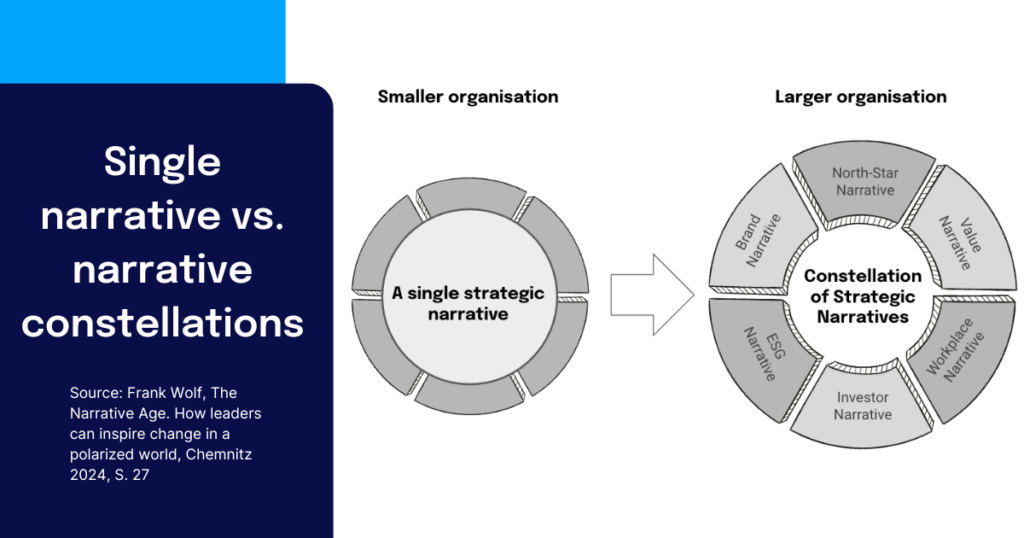

As an organization, you want to build a strategic narrative in the minds of your stakeholders. However, should this narrative be the same for everyone — employees, customers, investors, and the public? The answer is: it depends.

A small, emerging company might typically have just a single narrative. The founding idea simply needs to resonate with the group of founders, early customers, and investors. At this stage, and while the company grows to a certain point, a single strategic narrative may suffice.

For example, Google started with the idea of revolutionizing internet search. Just a few years after its establishment, the World Wide Web saw an explosion of information. Google’s core idea was to make the world’s knowledge more accessible. This strategic narrative was enough for the company to take off.

However, as organizations grow and become more powerful and impactful, they need to craft multiple narratives to address the specific needs of different audiences.

Google’s growth and increasing power in the market began to concern many people. As a result, Google needed a narrative to reassure the public that its mission was still aligned with its values and that it wasn’t becoming a monopolistic threat. This is where the “Don’t be evil” narrative came into play. Here is an example of several key narratives for Google. Together they create a constellation of strategic narratives.

Another example is the growing need over time to separate the overall vision — the company’s North Star — from a value narrative. As an organization attracts more customers, they may not be as interested in the long-term vision as they are in the short-term, immediate value they get from your products and services.

One example of this is something we experienced for ourselves at Staffbase. Our long-term strategic narrative is to build the first end-to-end communications platform to make companies and communication professionals highly impactful for their businesses. However, many of our customers start with just one channel, such as an employee app or an email newsletter. While they are interested in the long-term vision, they care much more about the immediate value they get for their work. So in this case, a combination of both narratives is needed.

In short, new companies or startups often have a simple way of describing their vision and, therefore, focus on one strategic narrative that they communicate to all stakeholders. However, as an organization grows, there will be an increasing need to develop more specific narratives for different audiences. In this context, a strategic narrative can be understood as a group of key narratives, often referred to as a “constellation” of narratives.

Strategic narrative and North Star narrative

If an organization is still smaller and operates with only one narrative, we could say that the strategic narrative and the North Star narrative are essentially the same. The focus is on the vision and mission of the company — this is the fundamental reason the company exists.

A strong organization always has a destination, something promising and new that attracts employees, customers, and investors. When focusing on a single strategic narrative, it will likely incorporate elements of a value narrative as well. So, this single strategic narrative will be a mix of a North Star narrative, a value narrative, and perhaps some other elements.

As the organization grows and begins to develop more narratives for specific audiences, it makes sense to still have the mission and vision at the core of all these strategic narratives. In this case, the set of strategic narratives is broader, but at its core is the North Star narrative.

One can assume that this North Star narrative is particularly compelling to employees for alignment and guidance, as well as to investors who, ideally, have a long-term vision and interest in the organization. Customers, on the other hand, may focus more on value and brand narratives, while the general public will pay closer attention to ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) narratives.

Why do strategic narratives matter for businesses?

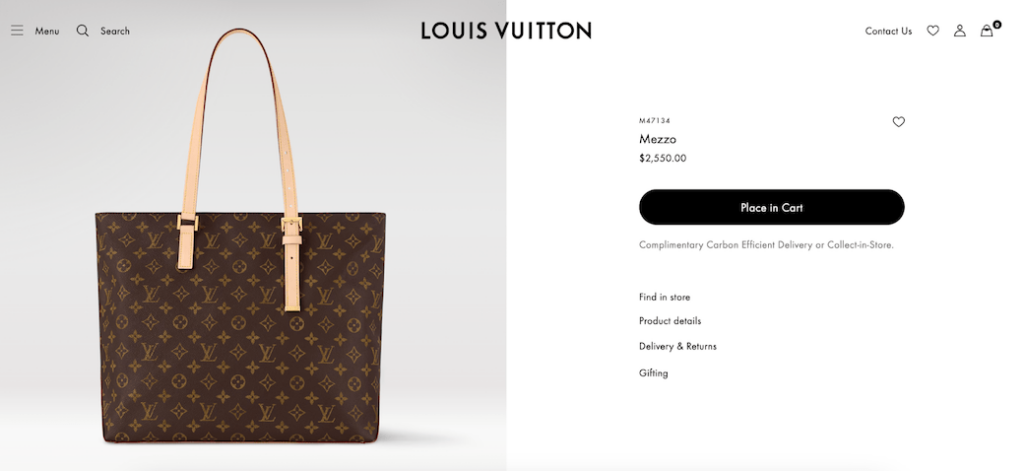

Let’s start with a simple example. Look at the price of this Louis Vuitton bag.

Why do people pay between $2,000 and USD 40,000 for Louis Vuitton bags when they cost between $200 to $800 USD on average to produce? Louis Vuitton marks up the price up to 2,000 percent, which means customers pay thousands of dollars for nothing more than — a narrative!

For Louis Vuitton customers, each purchase isn’t just a transaction; it’s an induction into a storied legacy. One of the key strengths of a narrative comes into play here. Remember, a story is mainly about other people, but a narrative is inclusive. That makes it possible to join the movement. I can buy a Louis Vuitton leather bag or a Tiffany’s necklace and acquire a piece of history and a status symbol. Purchasing a luxury good is an investment into an aspirational vision of ourselves.

The overall reputation of Louis Vuitton is fueled by a number of narratives: the design language, the materials, the shops, the celebrities, and the influencers who own the bags, and so on. Narratives build the reputation of an organization or individual.

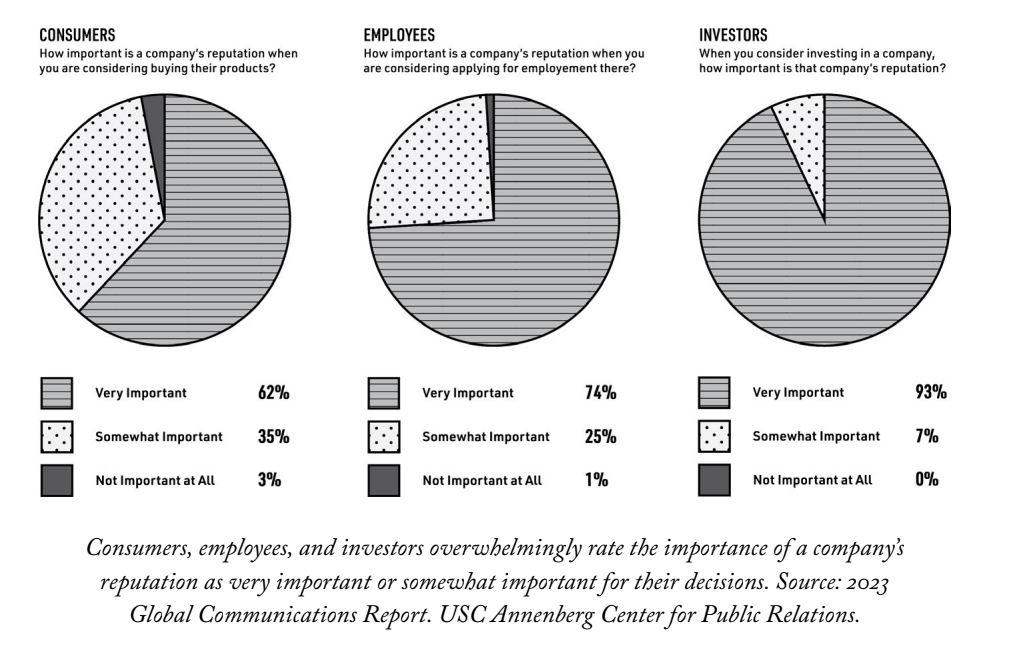

Narratives enable organizations to actively influence their reputation. By providing a cohesive context to individual stories, narratives link them together to create a bigger, more comprehensible picture of the organization. The benefit is not limited to charging higher prices for luxury goods — a great reputation will resonate positively with all stakeholders as these numbers from USC Annenberg Center for Public Relations prove.

How to define strategic narratives with narrative maps

The most important characteristic of a successful strategic narrative is that it needs to fit and resonate with the existing worldview of your audience. While researching narratives for my book, I came across many different types of existing beliefs that an audience could hold, and I sought an easy way to map all these narratives into one model. The result is a narrative map.

Here’s a concrete example of how a narrative map can be created and used to build a strategic narrative.

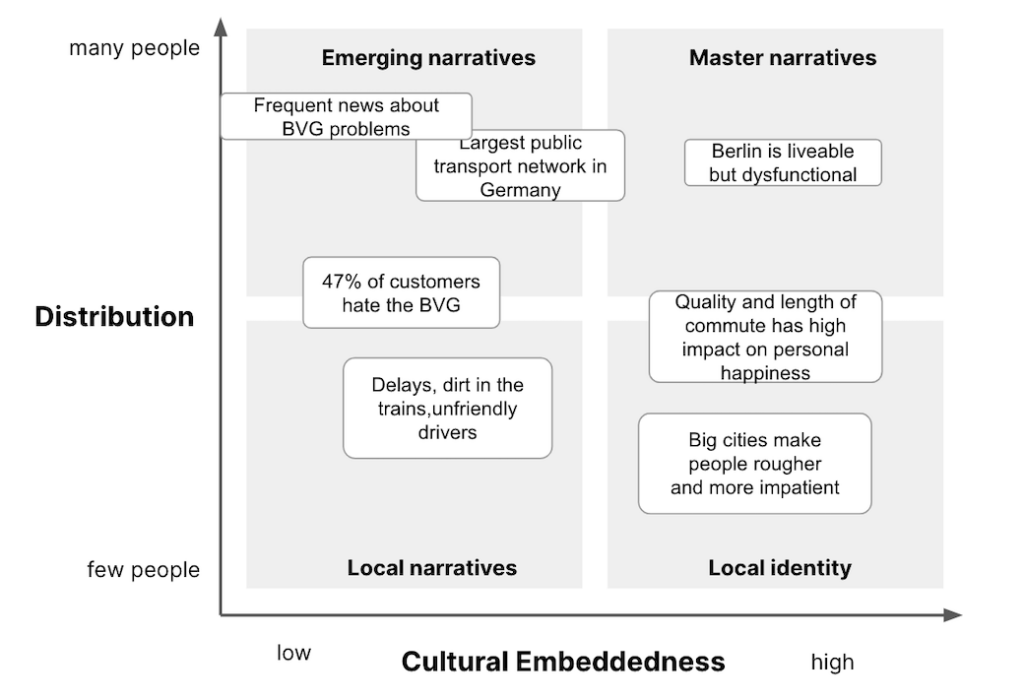

In 2015, Berlin Public Transport (BVG) faced a challenge. Despite numerous marketing campaigns, the sentiment around using BVG remained negative. Nearly 47 percent of its customers said they hated using the service.

However, changing the company’s service wasn’t an easy or immediate option. Buses were stuck in traffic like any other vehicle, and ordering a new subway car could take up to seven years from order to delivery. The issue was further complicated by the city’s increasing traffic, driven by its rapid growth.

So, instead of focusing solely on service modifications, BVG needed to invest in changing public perception.

To create a new value narrative for Berlin Public Transport (BVG), let’s consider the narrative map in this case. The map distinguishes four different basic types of narratives along two dimensions. This serves as the foundation for collecting existing narratives and strategizing how a new narrative might best fit into this established landscape.

The result was a campaign named “Because we love you” which aimed to make it fashionable again to use BVG transportation in Berlin.

The strategy was to craft messages that were self-critical and played with the very common perception that Berlin is liveable but sometimes a bit dysfunctional.

For instance, when Ringo Starr held a concert in Berlin, BVG’s advertisement humorously remarked:

Ringo Starr is in town. Finally, someone who’s worse at keeping time than we are.

Another example addressed the frustration impatient BVG customers had with ticket machines:

In Terminator 6, humans fight against machines. You can experience that every day at our ticket machines.

This type of messaging, which was echoed throughout their campaigns, resonated with Berliners. BVG acknowledged its shortcomings but also humorously held up a mirror to its customers.

The overarching narrative that BVG championed was:

“We are like Berlin. We may not be perfect, but we are genuine, lovable, and steadfast in our commitment. Every day, rain or shine, we are here for you.”

By aligning themselves with the authentic spirit of Berlin, BVG successfully bridged the gap between service expectations and the city’s inherent narrative landscape.

The results were stunning. From a Net Promoter Score of -10, BVG rose to +18. This change wasn’t just in numbers but also in public perception across all age groups. Ticket sales surged, with BVG’s growth rate doubling that of the city. This success was attributed not just to the service but also to the campaign.

And it didn’t just impact customers. For the BVG staff, the campaign had a significant impact too. Employees were proud to be associated with the company, feeling that the marketing was for them as well as customers. The campaign strengthened the employer brand and significantly increased job applications.

BVG’s journey from a negatively perceived public service to a beloved brand in Berlin underscores the power of understanding audience sentiment with a narrative landscape and building a strategic narrative with messaging that resonated perfectly, inspired customers, and transformed BVG’s image.

Case in point: The strategic narrative for SpaceX vs. Blue Origin

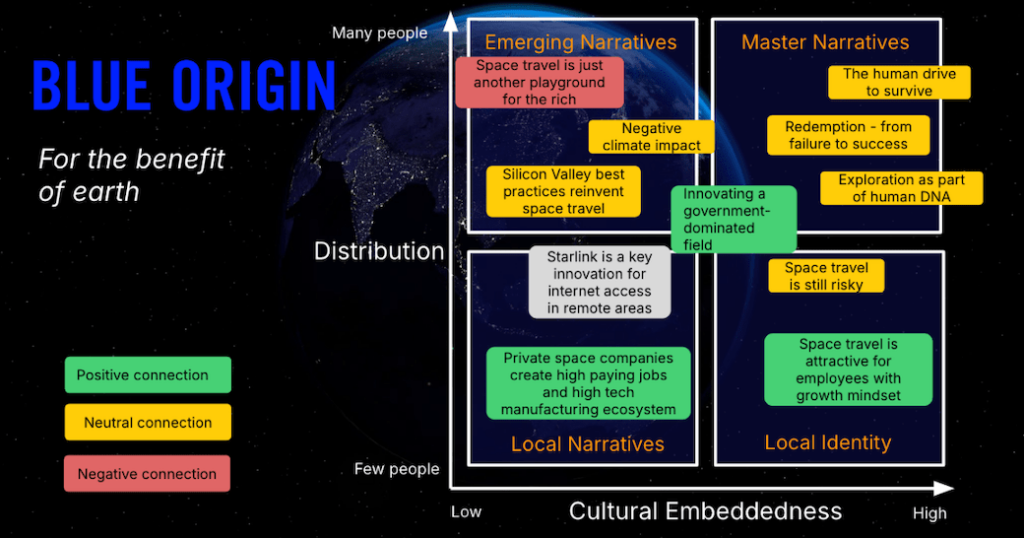

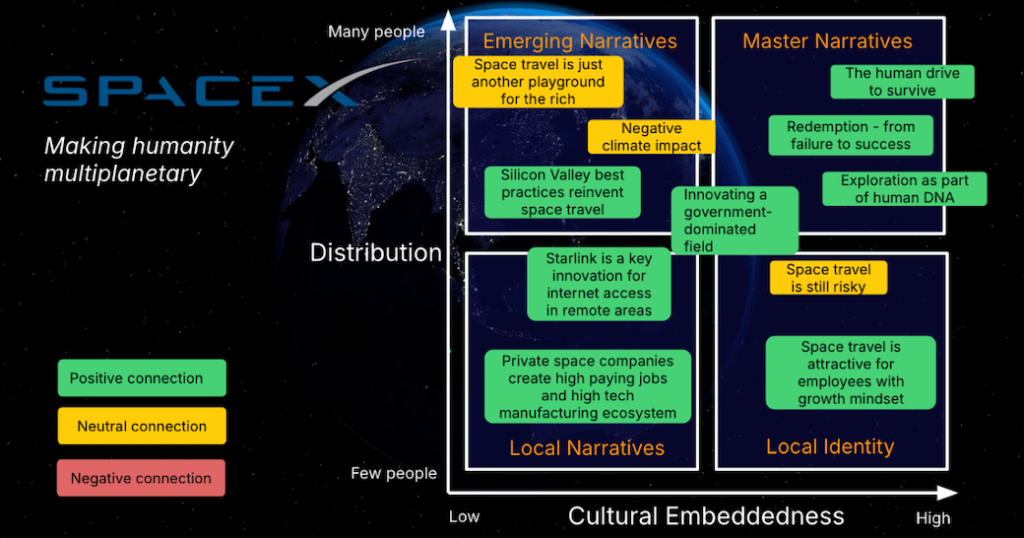

Blue Origin and SpaceX differ not just in their vision but also in their commercial approach and culture. These differences lead to a much better alignment of one of the two companies with the current and emerging narrative landscape for space travel.

Until now, Blue Origin has been very focused on space tourism. It can launch up to six people to the borderline between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space, where they will experience weightlessness for about 10 minutes at a price tag of about $1.25 million USD per seat.

SpaceX is further ahead

SpaceX also offers space tourism, but their main driver for launches is Starlink, a satellite-based high-speed internet service for people living in remote and rural locations around the globe. So far, the number of successful launches and the complexity of the missions completed speak in favor of SpaceX. Despite being founded two years later the company has achieved a great technological advantage over Blue Origin.

American theoretical physicist Michio Kaku argued that SpaceX has a “tremendous lead” over Blue Origin in regard to space exploration: “It’s not head-to-head like the media would like to portray, you know, the battle of the billionaires. SpaceX has a tremendous lead over Blue Origin. They’ve been around the Earth several times, they go to the space station . . . So none of this, going up for three minutes and coming back down. No, we’re talking about the moon now.”

Blue Origin’s vision statement misses the beginning of the narrative

Remember, a narrative has a basic structure of a beginning, a middle, and an end. It takes us on a journey from the status quo, through a catalytic event, ultimately resulting in a new normal. Many vision statements that fail to capture our attention have blurry goals about an end state, like becoming the market leader. But the beginning of a story does something that is vitally important: it makes us care. In the words of professional storyteller and coach Kindra Hall:

“A bad story has a single, defining characteristic. We don’t care. Even the flashiest of colors, the biggest of budgets, or the cutest of puppies can’t make us care. Fortunately, the majority of the time the root cause of this disconnect can be traced back to a single mistake, leaving out the first part of the story. The normal.”

The SpaceX vision makes us care because we are all aware of the beginning of the story: Humans have never set foot on another planet. We landed on the moon a couple of times, but that was decades ago, and to really begin to conquer our solar system, we need to travel to another planet. This is the beginning of the story. It is not specifically mentioned in the SpaceX vision, but that’s because it’s universal knowledge and part of the existing narrative landscape.

Compare that to the Blue Origin vision: What is the beginning of the story here? Is space travel being used for the first time for the benefit of Earth? There are already thousands of satellites orbiting Earth, benefitting our communications, weather data, navigation, and real-time observation. None of that is new. The Blue Origin vision isn’t just vague in terms of the goal or the end of the story. It also misses the beginning, the challenge that makes us care.

A great vision connects the present with the future and therefore needs the structure of a starting state, a catalyst, and an aspirational end state that we can relate to and picture in our mind.

The narrative landscape

Let’s look at the narrative landscape of space travel and how it fits to Blue Origin’s approach.

And here is the same analysis for SpaceX:

Overall, SpaceX achieves a significantly better fit to the narrative landscape. Both companies have been founded by iconic entrepreneurs, and they showcase the fact that private initiative and innovation can challenge the traditional model of centralized, government-directed space activity. SpaceX forges ahead with its compelling vision and stories that connect to the powerful and deeply rooted master narratives of exploration, redemption, and survival as a species.

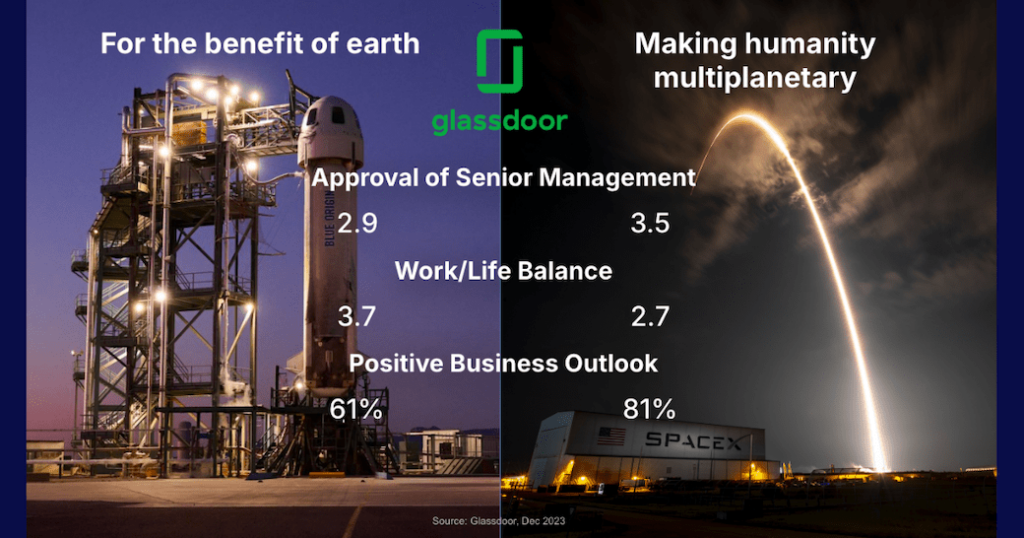

Is this subjective? Of course. But let’s consider the opinion of a group with the best insights into both companies: the employees. Thankfully, data is available from Glassdoor, a platform where employees provide public feedback on the companies where they work. Here is a comparison of three key dimensions.

Based on these numbers, SpaceX seems to be a workplace where employees are fairly confident that their leadership team will steer the company toward a positive future with the notable downside of less work/life balance.

Blue Origin creates a comparably better work/life balance, which is also reflected in many of the individual reviews. However, the leadership ratings and future outlook are significantly lower compared to SpaceX.

Blue Origin currently struggles to connect positively to the existing narrative landscape with its vision. It is still a very attractive employer, especially considering the employees’ much better work/life balance, but SpaceX might be the more attractive employer overall, especially for talent with a strong growth mindset. Over the long term, this can further extend the competitive advantage that SpaceX has today.

Blue Origin’s opportunity lies in securing contracts such as those awarded by NASA. This might provide new opportunities to better connect the vision to the narrative landscape and tell stories beyond space tourism. For example, an adapted vision from “For the Benefit of Earth” to “Exploring Space to Protect Earth” would already introduce a connection to the exploration master narrative and make clear that supporting our planet with insights and resources from space is not a nice-to-have but an essential part of the plan to allow humanity to survive and thrive on our blue origin.

Now, it’s your turn. How will you craft a strategic narrative that not only shapes your business but also inspires those around you to believe in a future worth building?

Strategic narratives continued

If you enjoyed what I shared today about strategic narratives, then I encourage you to pick up a copy of The Narrative Age where you can read much more about the power of narrative. You can also follow me on LinkedIn, where I’m happy to engage in conversations and discussions about the influence of narrative in modern organizations, such as measuring narrative impact in the modern business world. Lastly, I encourage you to check out Staffbase’s Mission Control to further discover how to coordinate and drive communications impact.