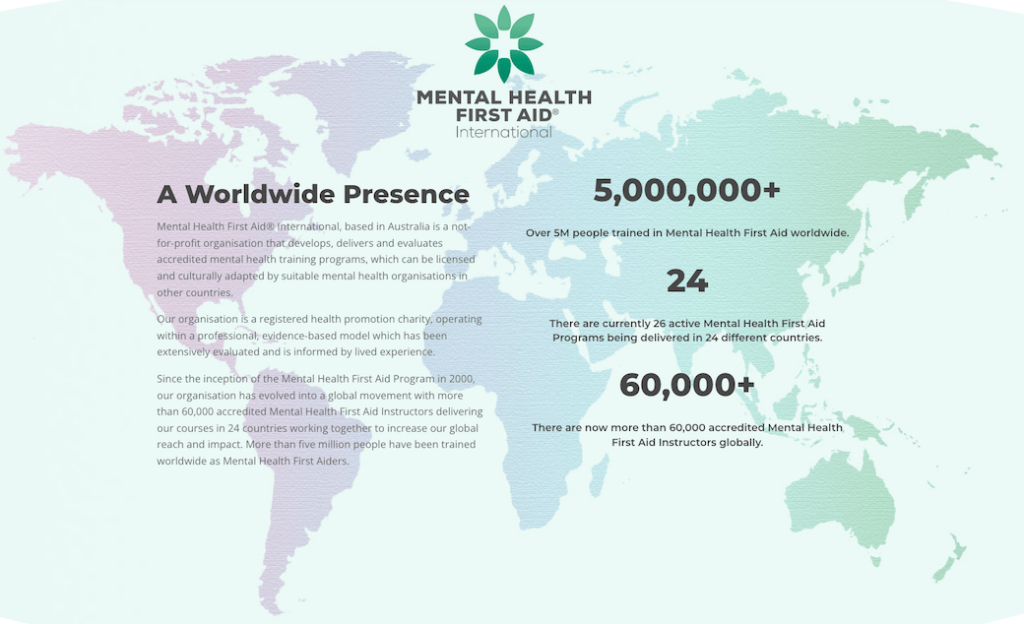

Mental Health First Aid International teaches members of the public how to help a person developing a mental health problem, experiencing a worsening of an existing mental health problem, or in a mental health crisis. Founded in Australia in 2000, Mental Health First Aid has since trained five million people worldwide from over 60,000 accredited Mental Health First Aid instructors. Today, a majority of their work happens in organizations looking to foster workplace mental health.

We spoke with Claire Kelly, an original MHFA instructor, about her experience developing the program. In particular, our discussion touched on the importance of supporting workplace mental health and the role internal communication plays in modeling positive mental health behaviors at work.

Tell us a bit about yourself and how you became involved with mental health first aid. Interestingly, I don’t have a psychology background. A lot of people assume that any of us involved in the mental health field do. I was actually an honors graduate from sociology. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. Also, I had a history of depression and anxiety that had started when I was a teenager and quite a strong history of mental health problems in parts of my family. It mattered to me, but I knew very, very little about it and certainly about what one could do.

I got a job as a research assistant at a mental health research center, not focused on clinical work. But the work that they were doing was really very new at the time. They focused on mental health literacy and how to get members of the public to understand the importance of mental health, to understand what mental illness is, and to reduce the stigma around it. The obvious next step from there was: What skills do people need to become mental health literate?

Back in 2001, Betty Kitchener, the founder of our organization, had run the very first mental health first aid course. It’s funny to me now, I heard about it and I thought, “God, that’s just so great. Why hasn’t anyone ever thought of this before?” Of course, that’s often what people say when they first hear about us. At the time, it was a small community project of Betty and her husband, Anthony Jorm. He’s one of the top five cited researchers in psychology and psychiatry worldwide.

They’d been talking about how it’s great that so many people get a first aid certificate. But most people will never use those skills. You’ve got to be in the exact right time, right place, all of that. If there was a little bit in there about mental health, everyone would use those skills because the rate of mental illness is so high.

Australia had just had our first national survey of mental health and wellbeing. It showed that about one in five Australian adults every year had a diagnosable mental illness. But the vast majority were not seeking help. At the same time, we’d had this first national mental health literacy survey. It showed that Australians knew very little about mental health.

This is it. This is what I want to do with my life. [This training] is going to make such a difference in the world and I want to be a part of that.”

Claire Kelly

Betty had just started running these courses. I was sitting in her fourth or fifth course, and I just had this feeling of, “This is it. This is what I want to do with my life. [This training] is going to make such a difference in the world and I want to be a part of that.”

Fortunately, I was also surrounded by a bunch of badass lady academics. Within a couple of months of my starting as a research assistant, they were all saying, “Just do your PhD. Get it out of the way, and then you can do all sorts of things.” I became a mental health first aid instructor while I was doing my PhD and continued to do whatever I could for Betty in terms of research assistant-type roles.

Then I was really fortunate to be offered a postdoctoral fellowship for us all to come to Melbourne together as a team. It’s funny, it was the whole team, but it was only four people. We were tiny back then and we still really didn’t know to what extent this might grow. By then we already had instructors in every state and territory of Australia. And we had also started to move overseas. Hong Kong and Scotland were the first two overseas licensees [and] after that, it just really accelerated.

Why do you think the training courses took off so quickly? I think it’s because there’s been a movement all around the world for us to have a better understanding of mental illness. But there’s been a lack of, “Here’s how you can help,” that goes along with it. Sometimes it’s platitudes, like “be present” for people. That’s not necessarily a very useful piece of advice to give. [It’s better] when you can give people really concrete advice on how to speak to people about what support they might need and get them to understand the benefits of seeking help without being in any way coercive or using any guilt trip.

We do cover suicide in our courses, [and] there’s always a tremendous amount of anxiety around that. People are very afraid of talking about suicide in case it gives somebody the idea, despite there not being any evidence that that could happen. Actually, quite the opposite. We know that when people have a chance to talk about their suicidal thoughts, they’re far less likely to act on them, [and] generally feel much less alone and much more supported.

Suddenly, here we were with expertise from Betty and Tony and their vast network of professionals: clinical, research, and education experts who were able to support the learning in the areas where perhaps they didn’t know everything. Then we started working on the guidelines projects, which was my postdoc.

Here in Australia, Rotary Health provides significant funding for mental health research. Including educational scholarships, postdoctoral fellowships, research funds, a lot of different things. And particularly supporting young researchers, indigenous researchers, and those sorts of groups.

A farmer had died by suicide in drought-stricken New South Wales. Rotary clubs in that area had all come together to raise money. They really wanted to do something that would have an immediate impact on the community.

They loved our application because we said, “This is not just research that’s going to sit on a shelf. We’re going to get out to your people and teach you how you can help someone who’s at risk of suicide.” Our evidence base grew, our reputation grew, and we were able to move into other areas. We launched a second course, our youth mental health first aid for adults supporting kids in their high school years. And our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander course for people in those communities.

Then we started a course for supporting older people, and a course for teenagers supporting each other. We’re now working on child mental health first aid. We now know so much more about the impact of poor mental health in childhood. Honestly, childhood mental health is what is going to help adults.

People often won’t seek help for themselves. [But] they will start to accept the idea that it might be a good idea once somebody they care about and who they perceive cares about them and is perceived to have some knowledge or authority says, ‘Hey, this is what I’ve noticed. I’d love to talk to you about it and I’d love to help you to get some help.'”

It’s wonderful that we have been a part of really pushing an agenda of action. It’s virtually impossible to ask for help. It is so hard, especially when you are overwhelmed by the symptoms of a mental health problem. People often won’t seek help for themselves. [But] they will start to accept the idea that it might be a good idea once somebody they care about and who they perceive cares about them and is perceived to have some knowledge or authority says, “Hey, this is what I’ve noticed. I’d love to talk to you about it and I’d love to help you to get some help.”

It’s funny, I know I’m mixing up how I got involved with how the program developed. But in a lot of ways, I feel as if you can’t untangle that. It’s been my whole professional life and it’s been wonderful to see what we’ve achieved. Already here in Australia, we’ve trained around a million people. We’ve trained around five million worldwide and our growth is exponential.

How does mental health first aid compare to traditional, physical first aid? There are some really important similarities, and one of them is that you are not taking things on yourself. We don’t learn how to do surgery when we attend a first aid course. Say you were a surgeon and somebody fell off a bicycle out in the street. You’re still not doing surgery. You’re still only doing first aid. It’s just a different level of skill and a different set of skills.

Mental health first aid is the help that’s given to a person who is developing a mental health problem, experiencing a worsening of an existing problem, or is in a mental health crisis. The help is provided until professional help has been received or the crisis has been resolved.

There are some really important differences. One that’s also a real opportunity is the fact that mental health problems don’t develop suddenly. That means you’ve got more than one opportunity to have a conversation with them. You can choose your moment.

It also might be that you’ve got some concerns about someone who is part of your circle. They could be in your private life or in your workplace. It might be someone who you don’t have a great relationship with. Maybe you really don’t feel that it would be beneficial for you to have the conversation. You can get somebody else to do it. You can have that conversation. Whereas if somebody falls off a ladder and breaks their ankle, they don’t have to have a great relationship with the person who wraps their ankle. They just want to know that the person providing the first aid has the ability to do that.

We would like to see some parity between first aid and mental health first aid. That could mean having a first aid officer for workplace mental health, the same way you’d have a physical first aid officer. [But] we think that that’s not enough. We actually feel that there really needs to be more people at different levels.

Imagine if you were the only mental health first aid officer having to support someone who reports to you. It’s immediately going to feel like, “Oh, my gosh, if this person is noticing my mental health, that means I’m in performance management.” And what if it’s the person you report to? That could not be more awkward. You need different people at different levels. The same in schools, we always say, don’t just train your senior staff. Often they won’t have as much time to have these conversations either. Think about the teachers and the school staff that the kids are most likely to talk to.

There are a couple of other important differences. Of course, first aid is always about a crisis moment. An accident, a heart attack, a stroke. It’s something that happens and you need to have that immediate response. You don’t have time to play with. But it’s also a much more tightly defined role in terms of the situation.

Imagine I am on the tram on the way home from the office and somebody has a heart attack. This actually happened to me a few years ago. You administer first aid and somebody calls an ambulance and the ambulance comes and takes the person to the hospital.

I wouldn’t go to the hospital with that person because I know that when they get there, the staff are going to say, “We’ve identified that there’s a heart problem. We have the right equipment. We know the medications to provide.” No one is going to say, “I’m just not sure that heart problems should be our problem. If people had better attitudes, they wouldn’t have heart problems.”

But when it comes to mental health first aid, we know that people can be treated quite poorly in some health settings. This happens especially in an emergency such as an episode of non-suicidal self-injury or when someone is having thoughts of suicide. Particularly if there’s been an ongoing pattern of that crisis occurring. We know that there isn’t the same stigma. The role of the mental health first aider is not only until professional help has been sought, but until it’s been received.

The role of the mental health first aider is not only until professional help has been sought, but until it’s been received.”

If I was providing mental health first aid to my best friend and he went to the doctor and afterwards he said, “Look, this doctor just told me to not watch television before I go to bed,” and didn’t seem comfortable talking about any of this, then my first aid role is not finished. I’ll support him to find a different GP with a little bit more knowledge and skill around mental health.

Why is workplace mental health such an important topic? There are so many different reasons. The first one is that we spend more time in the workplace, whether that’s virtual or physical, than we do at home. Certainly, we can spend more time with colleagues than we do at times with the people we live with. People can behave quite differently at work and at home. Perhaps somebody who has particular stressors can keep it together at home. But it’s actually at work where the mental health effects are really being felt.

In the very early days, Betty and I used to talk about the sorts of people who were seeking our training. They were often receptionists in GP offices and people who came into contact with welfare recipients experiencing stressors like financial distress. Obviously, people with those sorts of difficulties are much more likely to have a mental health problem. But we kept saying, “We want the hairdressers and the bartenders and the people who talk to anybody.”

It was probably about 10 or 12 years ago that the construction industry in Australia really began taking notice of mental health. That was wonderful because it’s a very male-dominated, “toughen-up” type of work environment. They were saying, “We’re starting to think that there might be some problems with our culture.” We were like, “Yes — there are many reports of a culture of bullying and substance use, high-pressure environments. Let’s get proactive about helping people get the support they need.”

Before that, it was very much about employees who might have a front-facing role where you needed to provide some help. Now, the majority of people who are looking to us want workplace mental health training. They want people to be able to support their colleagues.

Also, I think that we’ve got to remember that workplaces are communities of purpose. When they are running well, they will have workplace well-being programs. They may have connections with health services. They can destigmatize the use of different sorts of general counseling services through the use of employee assistance programs. In EAP, the people often aren’t clinical psychologists. But they will have counseling skills and the ability to say, “What I’m hearing is probably more serious. I’d like you to consider this referral pathway,” so that people have different ways in.

In workplaces, it’s often very acceptable to say, “Hey, do you want to go and get a cup of coffee?” You’ve got some of those opportunities as well. Also, I think we see changes over time. When we know that someone who has always been very good at their job — very conscientious, arrives at work on time — starts appearing to really lag, maybe they often don’t show up for work, or they show up but they’re not as productive, it’s really easy for people around them to think, “Ugh, it’s not fair. They’re not pulling their weight. This is having a terrible impact on all of us.”

But as soon as somebody actually is aware that it could be a mental health problem and it’s worth having a conversation, not only does the person have the opportunity to hopefully take steps towards getting better, but also the people around them can stop viewing them as somebody behaving poorly and having a negative impact on everyone to a more nurturing and empathic approach.

It’s not generally a great idea for someone to take a lot of time off work for a mental health problem. We know that in a healthy workplace, a positive workplace, that work is good for mental health. But if for a period of time someone reduces their hours or parts of their team perhaps take on a little bit more to reduce the load, all of those things have a positive impact on everybody around, not just the person suffering.

When somebody stands up and says, “This is what’s been going on with me. This is why I’ve been struggling and why I haven’t completed everything that I wanted to complete,” that also gives permission for others to do the same. If they then take that same behavior into their families and their friendship groups, everything becomes more acceptable.

I really love that we’ve gone from a bit of a compliance model where people were saying, “We have to do a mental health thing, so we thought we’d do you.” You can tell they’re just looking to tick a box. Now we have people coming in and saying, “We’ve got mental health first aid training. We’ve been doing it for a while. We want to know what we can do better. How can we integrate more of the principles into our daily work? What can we do to improve the culture here?”

It’s no longer a tick-a-box exercise. It’s a community of purpose, coming together to achieve something that can seep into other parts of the community. There are a lot of reasons why it’s really important.

Everyone wants to work. The cost of getting it right by being supportive and helping people to return to their previous level of functioning is better for workplaces financially and in terms of overall morale and for individuals. There’s a lot to benefit from.

[Mental Health First Aid] is no longer a tick-a-box exercise. It’s a community of purpose, coming together to achieve something that can seep into other parts of the community.”

PricewaterhouseCoopers ran a big analysis of the cost and benefit of various approaches to workplace mental health. They found that there’s about a $2.30 return on the investment of every dollar into an evidence-based mental health program. If you have to be data-driven about it, which we know in workplaces we have to be, it’s also a good financial decision.

It’s definitely important that the numbers are there when companies make these kinds of decisions. There’s always someone asking, “What’s the return on investment?” And that’s a valid question. Let’s talk about some of the communication skills that you teach. Sure. Look, communication is the key to mental health first aid. It’s about having a supportive conversation. I really like using that language as well because the conversation often goes from, “This is a person with a mental health problem. This is a medical condition for which they may need treatment. What on earth could I do that isn’t going to make things worse or isn’t going to upset or embarrass them?” to “I can have a supportive conversation.”

Communication is key to good workplace mental health

It’s also really important that it’s not so much about always saying the exact right thing. Rather, it’s about being genuinely caring and wanting to reach out. I think that’s incredibly important. The first thing is that you want to make an approach at a good time. We really don’t want to embarrass people. It’s not a good idea to call someone who might report to you and say, “Come to my office!” That immediately shoots the blood pressure up.

Find a good time and a place, ideally not on a Friday afternoon, when someone might then have to worry all weekend about how they might have come across. And somewhere that’s private, quiet, and where you won’t be interrupted. It’s not a five-minute chat. Although it might be. The person might actually say, “I can’t do this right now. Thanks for caring, but I can’t.” But it also might be an hour, so making sure you’ve got that time is really important.

It’s also really important that we listen in a very non-judgmental way. We can’t turn off our judgements. Our brains aren’t wired that way. It’s an essential survival skill being able to make snap judgments. But what we can do is be aware of when and where we might bump up against our judgements. Be prepared to set them aside in order to support someone.

It might be that a person is using substances where maybe you think, “Well, he should probably just stop doing that.” But it’s not helpful to think that way. Instead, recognize that, “Okay, well, that’s a thing that’s happening, but my concern is how this person is doing day-to-day. They appear to be very anxious or very sad, whatever it might be, that they’re not able to contribute. That’s what I’m going to focus on. Not the fact that I think they shouldn’t be using these substances.” Or it might be eating disorders. People often have this feeling of, “Well, if they weren’t so vain.” But it doesn’t work that way at all.

Setting those judgments aside is really important. It’s actually one of the reasons why I encourage people to think about what judgements they might come up against. Non-judgmental listening is really important.

I’ve got three questions that I will usually ask. The first one is going to be really open, just, “Are you okay? Is there something going on that you’d like to talk about?”

If the person says, “No, I’m fine,” then the next question might be, “Well, I’m a bit concerned about you and I’m open to discussing it.”

If they still say no, then the next step is going to be what you’ve noticed. “In all the time I’ve known you, you’ve always been really punctual and it seems like you’re coming in later and later over time. This is not a judgment about that time. But my concern is that it’s because you’re having a hard time getting going in the morning. Sometimes with depression or other mental health problems, that can be the case. I just want to find out what else is happening with you.”

Being able to have those conversations in a way that’s not about, “You are being a bad employee or a bad co-worker,” is very important. The same at home. It’s not about being a bad spouse or a bad parent or child, but, “I’m concerned about what I’ve noticed.”

This is not about giving advice. People generally don’t love advice that they haven’t asked for. In fact, public health evidence all says that if you tell people what to do, they won’t do it. But if you provide them information and options, they’re much more likely to make a better choice.

Instead of saying, “I think you should see a doctor,” try saying, “This sounds to me like you might be beginning to struggle with a mental health problem. Can I tell you a little bit about the sorts of professionals who might be able to help?” Not, “I think you should go on antidepressants,” but rather, “It might be helpful for you to know that there’s a range of different treatments that honestly do work and the evidence all supports that and a GP is a really good place to start.”

Doing that in a really very gentle way also allows the person the dignity of making those decisions for themselves. No one should ever be coerced. We always suggest that first aiders should have some information about services that are available. In a workplace, it might actually be workplace-related resources such as in the employee assistance program, if there is one. But also physically local resources.

Understanding that there are different options — even evidence-based self-help strategies that are available — can make a huge difference to somebody’s willingness to start making changes.

In organizations, we’ve seen that it’s often the job of internal communicators to initiate these kinds of conversations. But often the people charged with monitoring the mental health within their organization are neglecting their own mental health. How can internal communicators practice better self-care? Especially when they are the ones charged with ensuring the mental health of the people around them. Part of the problem is in your question: that it’s part of their role to “ensure” the mental health of people around them. Honestly, I think that for a lot of them, that is the way that they see it. They’ve got this responsibility and it sits solely with them. But it doesn’t.

It’s not helpful for anyone to be taking that on. I think people put on the cape and the big S on their chest to say, “Now, I’ve got these skills and these abilities, and I’ve got this role, and I can fix all of this.” It’s not just that they’re neglecting their own self-care. They’re probably not even aware that they need to care for themselves.

It’s like parenting experts with absolutely rebellious kids who drive them up the wall. Because suddenly it’s not a theory anymore. When you think about clinicians, you think about social workers, clinical psychologists, and psychiatrists. They all have some form of clinical supervision. It’s an essential part of their role. It’s a combination of therapy and professional development, and a whole lot of other things rolled into one where somebody is also able to keep an eye out for their mental health.

These are people at the top. People with less skill also still need that same supervision, but it doesn’t have to be a massive deal. Peer supervision models have been successful, and even communities of practice models can be successful in this. People with those roles, rather than being the superheroes and the secret keepers, can actually get together and say, “This week has been so crappy. I listened to this person and I feel that I did the right thing but it’s really brought me down. They’re in a really difficult situation, and I can’t fix it.”

When somebody says, ‘I can’t fix this,’ you want a peer around them to say, ‘It’s not your job to fix it.'”

When somebody says, “I can’t fix this,” you want a peer around them to say, “It’s not your job to fix it.” You’ve got to interrupt that because otherwise it’ll keep going. Whether there is an external one-on-one supervision type approach, or whether there is a facilitated peer supervision/community of practice approach, either of those can make a tremendous difference. I actually think that one of the best things that a workplace can do is ensure that they have well-being and self-care activities actually built into the workday that literally take time out of the workday.

One of my favorite things is a 15-minute mindfulness meditation, where people just jump in on Zoom for 15 minutes. There’s always something just a little bit different to think about. It’s on a Monday regularly and every week I think I don’t have the time. But I’ve committed to myself and my workplace that I will model as a leader and attend every week. Afterward, I think it was worth making that time. I’m less annoyed, less stressed, and ready to actually look at my to-do list instead of just crying into my notebooks.

When the workplace says this 15 minutes is sacred, then that’s actually incredibly powerful modeling. It’s a really good start if workplaces are in a position to do something like sponsored gym memberships for people who perhaps struggle to get exercise through the week. Exercise is one of the best evidence-based treatments for mild to moderate depression and anxiety available. Especially if you can combine that with doing something social, like a company softball team.

If the workplace says, “If you take an hour out of your week to go to the gym downstairs, that’s part of your workday,” that can make an incredible difference. If those listeners and communicators and people who have those sorts of responsibilities for well-being are seen as really taking advantage of those programs, then that’s excellent modeling.

When I say leaders, I don’t just mean in terms of organizational structure. I mean people who have the charisma or a pool that tends to influence others. Get them actively engaged in these well-being activities. Other people will follow, and it will stop feeling like slacking off.

I think we put a lot of status on saying, “I’m just too busy.” If somebody is too busy, if they’ve got too many meetings, then it must mean that they’re doing an amazing job and they’re super, super important. Everybody can find half an hour if they actually prioritize that and if they’ve been given permission to prioritize that.

Imagine if we could create workplace cultures where it’s actually better to do work for fewer hours and get more done and be more effective and more productive and happier than we are to cram work into every single second of every day.

I reckon that in the last couple of years we’ve actually gone backward in this area because a lot of the natural social things that we do in the workplace, just that five minutes of loitering in the hallway and talking about sports or what you did on the weekend. Those things were very natural. But somehow it feels a bit transgressive to jump onto a Zoom call to talk for 15 minutes about what you did on the weekend, so we’ve stopped doing it.

When people think, “Oh, I’ve got to make an appointment if I want to talk to Claire,” then they’re much less likely to do so. But if they know I’m in my office, they’ll just drop by. We’re out of practice in those natural social things. We can’t just expect them to go back to normal. We have to model getting them back to normal, and it’s not easy. Especially since the majority of workplaces have not gone back to full-time in the office.

There’s a lot that can be done. There’s no one solution.

I believe that every workplace that really engages with people at different levels should ask, “What do you think we should do?” People are going to come up with unique, interesting, culturally appropriate, and engaging ways to have those positive experiences. And in doing so we’ll also create more solid relationships where someone can actually say, “Hey, I’m concerned about you,” and the person that they say that to won’t be afraid to hear it.

We’ve talked a lot about the benefits of having people in a workplace, or in general, who know how to initiate these kinds of mental health conversations. In doing so, you’ve made a very good case for the kind of training that you provide. If someone reads this interview and comes away from it thinking, “That sounds like something I’d like to do,” how can they do that? How does one go about becoming an accredited mental health first aider? There are as many answers to that question as there are licensees around the world. There is some variety to the models that are available globally. I’d say get in touch with our Mental Health First Aid organization in your country. Find out about publicly available courses or how to seek an instructor to perhaps come into the workplace.

Really think about the size of your workplace and the number of locations. Obviously, in a small company, it’s not going to take very long. When you’ve got a few hundred up to a couple of thousand, it’s definitely worth thinking about who you might have on staff who might be a good mental health first aid instructor.

I would suggest looking at the MHFA International website, mhfainternational.org. From there, you can find links to all of the local licensees. In some smaller countries, the licensee directly runs all of the training. In others, there’s a devolved model like ours where there are instructors located all around the country.

It’s actually been really, really wonderful in the last few years. The number of licenses that we have in Europe has increased to the point where they have great relationships amongst themselves and a multinational European organization. Getting in touch with one of those organizations you’ll probably find that there’s someone who can put you in touch with others who could run training in different settings.

Well, that’s great to know. Thank you very much. This has been a wonderful conversation, and you’ve shared a lot of valuable information. I really appreciate an interview that becomes a conversation. I’d be very, very happy to talk to you again.

For more on mental health first aid, make sure to join us for a LinkedIn Live discussion with Claire, Rob, and Ralf Junge-Pearl, Head of Content at Staffbase. They’ll be answering your questions in real-time, so don’t miss out!

And if you’re looking for more practical mental health resources, we’ve got your back:

- Join our resilience email course, put together by Ralf — who, on top of leading our content team, is also a certified resilience trainer. You’ll receive four emails on how to understand your emotions and reactions to stress and, ultimately, how to protect your mental health at work.

- Let’s continue the conversation in Comms-unity, our Slack group for internal comms pros from around the world. Join the #mental-health channel to share your thoughts. How have you seen mental health first aid in practice in your workplace?